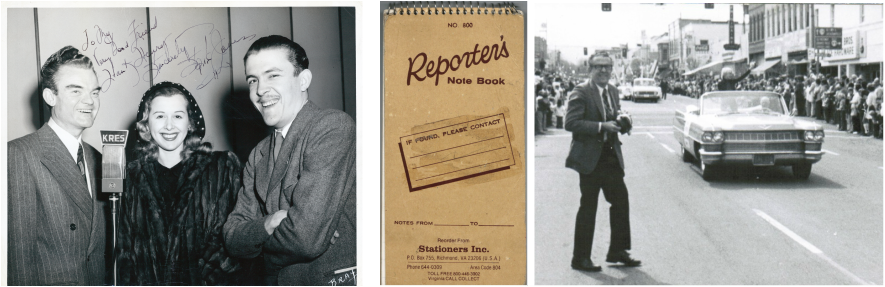

My Dad, Hank Henry

Click here to learn more about my dad, the TV broadcaster Hank Henry.

And here's a link to a column my dad wrote about being the only person in the audience when Nat King Cole recorded Mona Lisa.

And here's a link to a column my dad wrote about being the only person in the audience when Nat King Cole recorded Mona Lisa.

Choosing to Stop

(Based on an essay I wrote 10 years ago, shortly after my father's death at 80.)

This year, my father would have turned 90.

Ten years ago, my family made a decision we have never regretted. Ten years ago we asked that my father be allowed to die.

No one at the hospital suggested we stop aggressively treating my 80-year-old father. Even as test after test came back negative, even as he continued to deteriorate. He asked my brother Joe where Joe was, asked my mom what time the curtain would go up, and thought it was 1902.

He had long suffered from Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, his life a narrow circle from bed to living room, navigated by his walker. There were times his brown eyes were full of love, and times when they were blacker, lost, blank. Then a sudden illness began to ravage his body. In the hospital, he was put on three antibiotics. Still his skin was so clammy from fever that each new nurse recoiled when she first touched him.

I made a list of questions for his doctor – What was my father’s diagnosis? His prognosis? Why did his white blood count keep climbing? Why did he cry out whenever they moved him? And a few days later I added - What could we stop? - to my list of unanswered questions.

To the hospital staff, my father was no longer a person, but a series of problems. His unrelenting diarrhea indicated a bowel infection. But when the sigmoidoscopy turned up negative, the specialist only shrugged when I asked what was wrong. “Who knows why?” I wrote down carefully. The doctor who admitted Dad concentrated on getting his fever down. The nurses wanted to see if my father was ‘oriented.’ “Hank?” one cajoled him, prodding his shoulder while he stared at me with sagging, rheumy eyes. “Hank, do you know who this young lady is?”

I wanted to tell her to stop poking him, to leave him alone, to stop us both looking at each other with embarrassed eyes. Finally, my dad mumbled something like “Mary once or twice.” Or was it Merry? Or Marry?

My name is April.

He slept more and more, sometimes moaning. When he woke, he might say a few words, and I would think, I have to remember this. These might be his last words. And then he would mumble something else.

The social worker and discharge planner discussed the options with us, which I dutifully wrote down. If my father got better and seemed capable of rehabilitation, he could go to a skilled nursing facility. This was meant, the discharge planner explained, strictly to be transitional. Dad would have to be able to participate in physical therapy. At this point, my father couldn’t participate in rolling over. Parkinson’s had frozen his legs. When he was first admitted, Joe had tried to push Dad’s legs, hovering a few inches above the bed, down onto the mattress – at least until my father screamed.

If Dad didn’t meet the criteria for a skilled nursing facility, he could go to a nursing home. Or home to my mother, who had already injured her hip and back trying to lift him – from the toilet, the bed, the bath, the chair. And that was when he knew who she was, where he was.

Even as it became clear that he would probably never be coherent again, never walk again, never be anything more than a confused, bed-ridden person waiting for pneumonia to settle into his lungs, no one talked about just – stopping. Not the doctors, not the nurses, not the social worker. My dad talked about it without words. Even when coaxed, he ate nearly nothing. He closed his mouth and turned his head. His body began to forget how to swallow even water.

There was one horrible day when dad began crying out in pain - luckily my mom was at the bank getting into their safe deposit box - and I could not get the nurses to speed along the process for getting morphine. I would go out and beg, and the nurse would chirp that she had paged the doctor. Then I would have to go back to the room, go back to his muffled screams.

My brother and I started to have conversations that began, “If you had a cat this sick…” and then our words would trail off. What kind of children were we?

We finally steeled ourselves to talk with my mom. She found my dad’s living will. Step by step, it spelled out all possible interventions. And in all cases, my dad had initialed that he did not want them. My father’s final gift was to take the decision out of our hands, or at least make it easier for us to release him.

Now we had to tell the hospital personnel. I found his young nurse and told her we wanted to stop everything, including the IV fluids. With wide eyes, she said, "Then your father’s going to have to drink a lot more!" Feeling like the angel of death, I explained what I meant. We wanted my father to die. The doctor grasped it more quickly. But why hadn’t he brought it up himself? He had a copy of my father’s living will. He knew my father’s wishes.

On the fourth day of no IV fluids and no antibiotics, my brother called me. The doctor had been by and said Dad’s heart and lungs sounded good. I felt awful. No matter how much I reasoned with myself – But he can’t even swallow! But he’s too weak to even sit up! But he has a catheter and keeps having attacks of diarrhea on his bedclothes! – I would think, maybe we should have tried harder.

A few hours later, my father died. My mother was holding his hand, with classical music playing softly in the background. I realized he died the way he would have wanted, and the way he lived, quietly and with dignity.

About the last thing my father said to me was, “You learn how to do it just by doing it.” And he was right. My father learned how to die, and we learned how to fight, not for his life, but for his right to die.

This year, my father would have turned 90.

Ten years ago, my family made a decision we have never regretted. Ten years ago we asked that my father be allowed to die.

No one at the hospital suggested we stop aggressively treating my 80-year-old father. Even as test after test came back negative, even as he continued to deteriorate. He asked my brother Joe where Joe was, asked my mom what time the curtain would go up, and thought it was 1902.

He had long suffered from Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, his life a narrow circle from bed to living room, navigated by his walker. There were times his brown eyes were full of love, and times when they were blacker, lost, blank. Then a sudden illness began to ravage his body. In the hospital, he was put on three antibiotics. Still his skin was so clammy from fever that each new nurse recoiled when she first touched him.

I made a list of questions for his doctor – What was my father’s diagnosis? His prognosis? Why did his white blood count keep climbing? Why did he cry out whenever they moved him? And a few days later I added - What could we stop? - to my list of unanswered questions.

To the hospital staff, my father was no longer a person, but a series of problems. His unrelenting diarrhea indicated a bowel infection. But when the sigmoidoscopy turned up negative, the specialist only shrugged when I asked what was wrong. “Who knows why?” I wrote down carefully. The doctor who admitted Dad concentrated on getting his fever down. The nurses wanted to see if my father was ‘oriented.’ “Hank?” one cajoled him, prodding his shoulder while he stared at me with sagging, rheumy eyes. “Hank, do you know who this young lady is?”

I wanted to tell her to stop poking him, to leave him alone, to stop us both looking at each other with embarrassed eyes. Finally, my dad mumbled something like “Mary once or twice.” Or was it Merry? Or Marry?

My name is April.

He slept more and more, sometimes moaning. When he woke, he might say a few words, and I would think, I have to remember this. These might be his last words. And then he would mumble something else.

The social worker and discharge planner discussed the options with us, which I dutifully wrote down. If my father got better and seemed capable of rehabilitation, he could go to a skilled nursing facility. This was meant, the discharge planner explained, strictly to be transitional. Dad would have to be able to participate in physical therapy. At this point, my father couldn’t participate in rolling over. Parkinson’s had frozen his legs. When he was first admitted, Joe had tried to push Dad’s legs, hovering a few inches above the bed, down onto the mattress – at least until my father screamed.

If Dad didn’t meet the criteria for a skilled nursing facility, he could go to a nursing home. Or home to my mother, who had already injured her hip and back trying to lift him – from the toilet, the bed, the bath, the chair. And that was when he knew who she was, where he was.

Even as it became clear that he would probably never be coherent again, never walk again, never be anything more than a confused, bed-ridden person waiting for pneumonia to settle into his lungs, no one talked about just – stopping. Not the doctors, not the nurses, not the social worker. My dad talked about it without words. Even when coaxed, he ate nearly nothing. He closed his mouth and turned his head. His body began to forget how to swallow even water.

There was one horrible day when dad began crying out in pain - luckily my mom was at the bank getting into their safe deposit box - and I could not get the nurses to speed along the process for getting morphine. I would go out and beg, and the nurse would chirp that she had paged the doctor. Then I would have to go back to the room, go back to his muffled screams.

My brother and I started to have conversations that began, “If you had a cat this sick…” and then our words would trail off. What kind of children were we?

We finally steeled ourselves to talk with my mom. She found my dad’s living will. Step by step, it spelled out all possible interventions. And in all cases, my dad had initialed that he did not want them. My father’s final gift was to take the decision out of our hands, or at least make it easier for us to release him.

Now we had to tell the hospital personnel. I found his young nurse and told her we wanted to stop everything, including the IV fluids. With wide eyes, she said, "Then your father’s going to have to drink a lot more!" Feeling like the angel of death, I explained what I meant. We wanted my father to die. The doctor grasped it more quickly. But why hadn’t he brought it up himself? He had a copy of my father’s living will. He knew my father’s wishes.

On the fourth day of no IV fluids and no antibiotics, my brother called me. The doctor had been by and said Dad’s heart and lungs sounded good. I felt awful. No matter how much I reasoned with myself – But he can’t even swallow! But he’s too weak to even sit up! But he has a catheter and keeps having attacks of diarrhea on his bedclothes! – I would think, maybe we should have tried harder.

A few hours later, my father died. My mother was holding his hand, with classical music playing softly in the background. I realized he died the way he would have wanted, and the way he lived, quietly and with dignity.

About the last thing my father said to me was, “You learn how to do it just by doing it.” And he was right. My father learned how to die, and we learned how to fight, not for his life, but for his right to die.